This story was originally published by Floodlight, a non-profit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

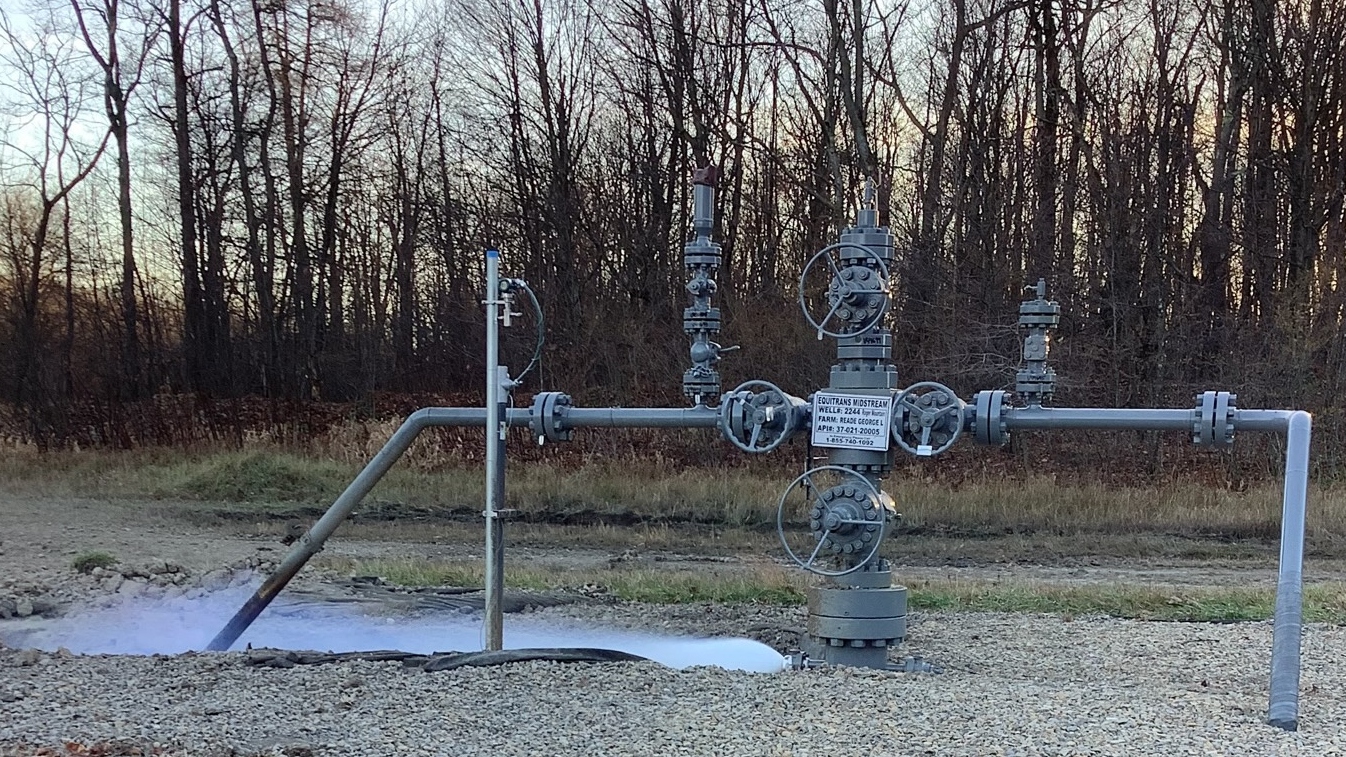

On a November afternoon in 2022, a 57-year old well tapped into an underground natural gas storage reservoir in western Pennsylvania started leaking, fast enough that people a few miles away heard a loud, jet engine-like noise.

By the time the leak was stopped nearly two weeks later, roughly 16,000 metric tons of methane had escaped into the atmosphere, the equivalent of more than the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 300,000 gas-powered cars.

The blowout of a well at the Rager Mountain gas storage field was the worst methane leak from underground storage since Aliso Canyon in California in 2015. That incident forced thousands of people from their homes and sickened many of them, taking four months to contain. In 2021, 35,000 plaintiffs in one class-action lawsuit were awarded up to $1.5 billion in damages.

While not as large or imminently dangerous to residents, the Rager Mountain leak was a “disaster,” according to one Pennsylvania regulator. Bloomberg labeled it the United States’ worst climate disaster that year.

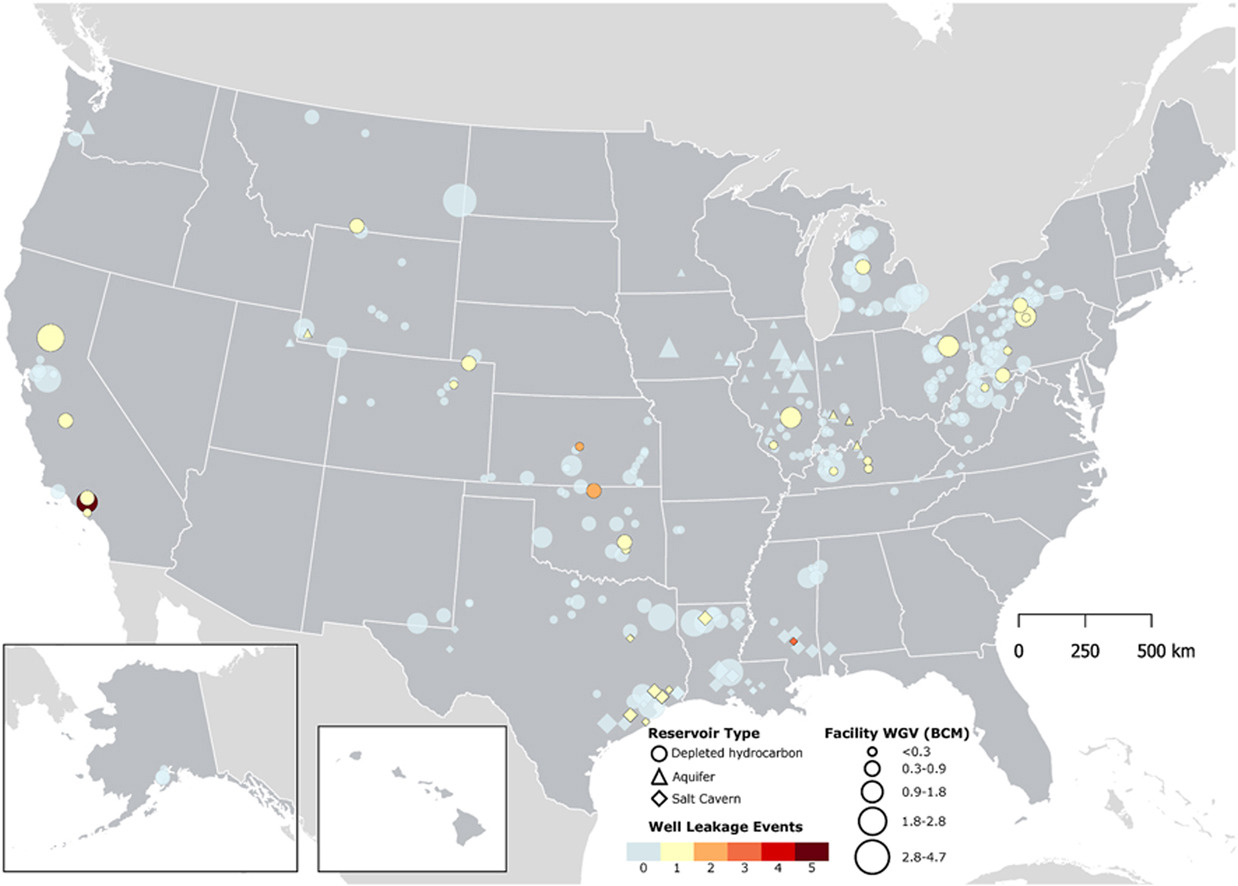

The natural gas that leaked methane in Pennsylvania and California is not stored in tanks but in giant underground geological formations accessed by multiple wells. There are about 400 such storage fields across 32 states.

According to a new report, there are thousands more potential opportunities for a similar situation across the country. The new analysis of data collected by federal regulators suggests there are as many as 11,446 storage wells in the country with the same key risk as the wells that failed at Rager Mountain and Aliso Canyon: They have only a single barrier to failure.

“That population is a lot larger than we had estimated, or other researchers had estimated with state [data],” says Greg Lackey, an author on the study and researcher at the Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory.

All but one of Pennsylvania’s 49 gas storage fields has at least one potential single point of failure well, researchers found.

Natural gas is primarily made up of methane, a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide in the short term. Methane leaks from oil and gas infrastructure are under increasing scrutiny in the United States and worldwide, as stopping them represents a relatively cheap and effective way to prevent greenhouse gas emissions, the primary cause of global warming.

Leaks from gas storage are only one part of the industry’s methane problem. Such facilities also are at risk of dramatic blowouts that are hard to control because they are connected to large, pressurized reservoirs of gas.

New rules and fees aim to cut methane leaks

Regulations put in place on gas storage post-Aliso Canyon are still rolling out, including a requirement for baseline risk assessments on all wells by 2027. New EPA rules on methane leaks and repair and a planned federal fee on “waste” methane would impact gas storage as well.

The fee, which is still being finalized, would force companies to eventually pay up to $1,500 per metric ton of methane in excess of the equivalent of 25,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide, a threshold the Rager Mountain leak meets almost 20 times over. Industry groups have pushed back against the fee, arguing it would harm smaller oil and gas companies and discourage oil and gas production overall.

Many of these wells are decades old and not originally designed for storage. They have gone through the stresses of repeated cycles of injecting and withdrawing gas. Some, like Rager Mountain, are in relatively rural, sparsely populated areas, but others are close to neighborhoods in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and California.

The Rager Mountain leak was caused by a break below ground in one well’s casing — the barrier between where pressurized gas flows and the geology around it. The well had become heavily corroded from exposure to water, air, and organic matter through an open valve, according to a third-party analysis submitted to regulators and obtained through a public records request.

“They probably didn’t realize it, but they were creating an optimum case for corrosion,” says Dan Arthur, president of the engineering and technical services firm ALL Consulting, who reviewed the analysis.

Arthur says older wells in storage fields haven’t been given “as much significance” as they should be, and operators need to make sure they’re fully addressing well integrity.

“Age is a risk factor that you have to consider, but it also depends on how you are caring for the well,” he says. Redundant barriers reduce the risk of methane escaping if the well casing fails, Arthur and Lackey say.

Minimum federal safety standards on underground storage fields were set less than a decade ago in the aftermath of the Aliso Canyon leak. One of the federal agencies in charge of regulating gas storage sites, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), only began collecting regular data on underground storage fields in 2017.

More data needed to identify riskiest wells

The number of wells with potentially only one barrier was three times larger than previously estimated before the PHMSA data became available, Lackey says. This “single point of failure” design featured in both the Rager Mountain and Aliso Canyon blowouts is present in as many as 64 percent of all gas storage wells in the United States, his research found.

But the data reported to PHMSA is not enough to confirm how many of these wells actually have a single point of failure that would flag wells at the highest risk of another blowout, Lackey says. Researchers would need more information about each well’s design and construction, he says.

Geoenergy Science and Engineering, March 2024

“What you don’t get insight into is how many other casings there are, or where the locations of cement are,” Lackey says, describing additional barriers that would lower the risk.

Rager Mountain’s owner and operator, Equitrans, had its own risk ranking of storage wells, according to the third-party analysis. While Rager is the company’s largest field in Pennsylvania, its wells were not the highest ranked in the company’s own risk management plan — others were higher up the list because of their proximity to residential areas.

Both Peoples Natural Gas, the previous owner of the field, and Equitrans “recognized that corrosion was an issue,” so the companies used probes, known as “logs,” to examine the integrity of the well casings. But, the analysis noted, “Such a strategy is dependent on the logging being reasonably accurate.”

A 2016 test of the casing wall of the well that eventually failed underestimated its corrosion, the report says. When Equitrans reran the test after the blowout using an updated algorithm, it showed far more corrosion.?

In the wake of the Rager Mountain blowout, Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection said it was considering a “top to bottom review” of the state’s gas storage industry. Pennsylvania is one of a handful of states that have their own regulations covering gas storage.

“Everything is on the table for consideration in terms of making sure this industry is regulated appropriately and the public is protected and the environment is protected from potential incidents like this happening again,” said Kurt Klapkowski, acting deputy secretary for DEP’s Oil and Gas Management office, a month after the incident.

‘A huge battery system’

But after a successful effort by Equitrans to move the bulk of the incident investigation to federal regulators, DEP appears uncertain or unable to move forward with such a review. Klapkowski told the agency’s Oil and Gas board in September that regulators were “trying to figure out where our jurisdiction ends or might be preempted by the federal government.”

Pennsylvania DEP’s investigation into surface and groundwater contamination at Rager Mountain is ongoing, the agency said in an emailed statement, and it “remains committed to its goal of inspecting storage field wells on an annual basis regardless of risk.”

Wells are assessed through surface inspections and information reported by operators, DEP added, using multiple factors to prioritize wells for inspection, including the potential environmental impact and likelihood of failure, as well as proximity to population.

Equitrans has taken several steps to reduce risk in its storage fields, spokesperson Natalie Cox said in an emailed statement. They include reprocessing older well tests, running additional tests on another 100 wells in 2023, and changing its requirements for when to add protective gel to reduce corrosion. The company did not answer questions about whether these tests led to any well replacements.

Lackey’s study also found that nationally, while most leaks from gas storage were connected with accidents or well improvement projects known as workovers, leaks from corrosion released a much larger volume of methane.

“If it’s a valve or something that’s broken off on the wellhead, that might be easier to contain, rather than something downhole that would be exposed to higher pressures within the well,” he says. “During workovers you have systems in place to contain the well … whereas with corrosion, that’s something going on silently in the background.”

While a 2016 government task force recommended phasing out single point of failure of wells, ultimately the federal minimum standards only required operators to address them through submitting risk-management plans to federal regulators — plans that are not public.

The release of gas from Rager Mountain in November 2022 represented about 15 percent of the field’s working storage volume. Underground storage fields act as “a huge battery system,” says Drew Michanowicz, a researcher who has studied their proximity to residential areas.

Major leaks from storage not only release huge volumes of greenhouse gases but also reduce reliability in areas where natural gas dominates home heating and electricity production, Michanowicz says.

The federal leak investigation at Rager Mountain remains open at least until regulators review work on fixing three temporarily plugged wells in the field, likely in the spring. But Rager Mountain is otherwise operating. In October, with PHMSA’s approval, Equitrans began injecting gas into the field for the winter.

This story was produced with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.