The House this week overwhelmingly passed legislation meant to speed up the development of a new generation of nuclear power plants, the latest sign that a once-contentious source of energy is now attracting broad political support in Washington.

The 365-to-36 vote on Wednesday reflected the bipartisan nature of the bill, known as the Atomic Energy Advancement Act. It received backing from Democrats who support nuclear power because it does not emit greenhouse gases and can generate electricity 24 hours a day to supplement solar and wind power. It also received support from Republicans who have downplayed the risks of climate change but who say that nuclear power could bolster the nation’s economy and energy security.

“It’s been fascinating to see how bipartisan advanced nuclear power has become,” said Joshua Freed, who leads the climate and energy program at Third Way, a center-left think tank. “This is not an issue where there’s some big partisan or ideological divide.”

The bill would direct the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which oversees the nation’s nuclear power plants, to streamline its processes for approving new reactor designs. The legislation, which is backed by the nuclear industry, would also increase hiring at the commission, reduce fees for applicants, establish financial prizes for novel types of reactors and encourage the development of nuclear power at the sites of retiring coal plants.

Together, the changes would amount to “the most significant update to nuclear energy policy in the United States in over a generation,” said Representative Jeff Duncan, Republican of South Carolina, a lead sponsor of the bill.

In the Senate, Republicans and Democrats have written their own legislation to promote nuclear power. The two chambers are expected to discuss how to reconcile their differences in the coming months, but final passage is not assured, particularly with so many other spending bills still in limbo.

“If Congress was functioning well, this is one of those bills you’d expect to sail through,” said Mr. Freed.

Nuclear power currently generates 18 percent of the nation’s electricity, but only three reactors have been completed in the United States since 1996. Although some environmentalists remain concerned about radioactive waste and reactor safety, the biggest obstacle facing nuclear power today is cost.

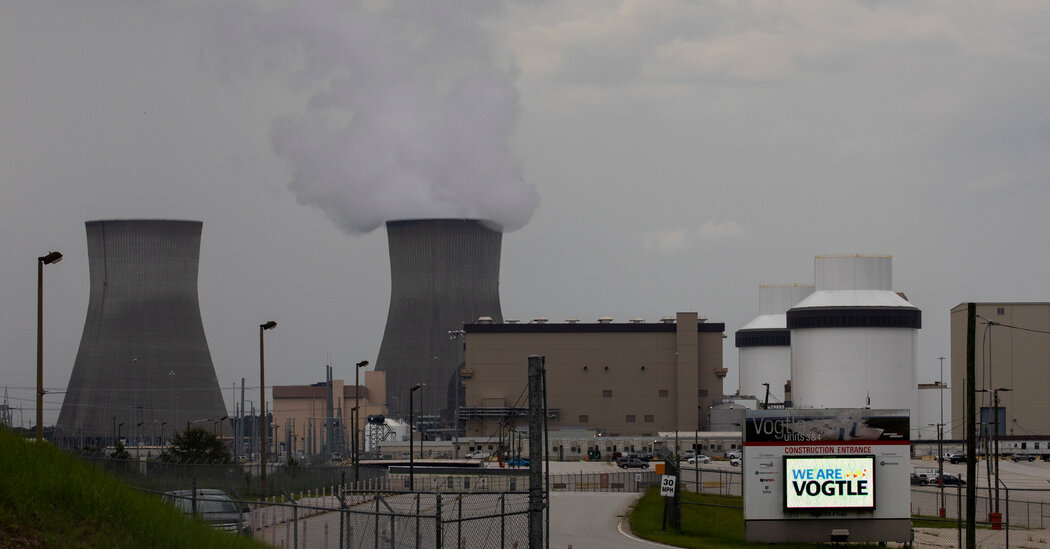

Conventional nuclear plants have become extremely expensive to build, and some electric utilities have gone bankrupt trying. Two recent reactors built at the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia cost $35 billion, double the initial estimates.

In response, nearly a dozen companies are developing a new generation of smaller reactors a fraction of the size of those at Vogtle. The hope is that these reactors would have a smaller upfront price tag, making it less risky for utilities to invest in them. That, in turn, could help the industry start driving down costs by building the same type of reactor again and again.

The Biden administration has voiced strong support for nuclear power as it seeks to transition the country away from fossil fuels; the Department of Energy has offered billions of dollars to help build advanced reactor demonstration projects in Wyoming and Texas.

But before a new reactor can be built, its design must be reviewed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Some Democrats and Republicans in Congress have criticized the N.R.C. for being too slow in approving new designs. Many of the regulations that the commission uses, they say, were designed for an older era of reactors and are no longer appropriate for advanced reactors that may be inherently safer.

“Tackling the climate crisis means we must modernize our approach to all clean energy sources, including nuclear,” said Representative Diana DeGette, Democrat of Colorado. “Nuclear energy is not a silver bullet, but if we’re going to get to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, it must be part of the mix.”

Among other changes, the House bill would require the N.R.C. to consider not just reactor safety but also “the potential of nuclear energy to improve the general welfare” and “the benefits of nuclear energy technology to society.”

Proponents of this change say it would make the N.R.C. more closely resemble other federal safety agencies like the Food and Drug Administration, which weighs both the risks and benefits of new drugs. In the past, critics say, the N.R.C. has focused too heavily on the risks.

But that provision updating the N.R.C.’s mission was opposed by three dozen progressive Democrats who voted against the bill and said it could undermine reactor safety. The specific language is not in the Senate’s nuclear bill.

Even if Congress approves new legislation, the nuclear industry faces other challenges. Many utilities remain averse to investing in novel technologies, and reactor developers have a long history of failing to build projects on time and under budget.

Last year, NuScale Power, a nuclear startup, announced it was canceling plans to build six smaller reactors in Idaho. The project, which had received significant federal support and was meant to demonstrate the technology, had already advanced far through the N.R.C. process. But NuScale struggled with rising costs and was ultimately unable to sign up enough customers to buy its power.