Hello, and welcome to the first issue of State of Emergency, a limited-run newsletter from Grist. My name is Zoya Teirstein, and I’ll be co-reporting this project with my colleague Jake Bittle. We’re glad you’re here.

Data shows that while some voters rank climate change among their top political priorities, it rarely factors into their decisions on Election Day. More than anything else, the health of the economy — and, perhaps more importantly, voters’ perceptions of it — typically dictates which candidates garner the most votes. But that doesn’t mean climate change is entirely absent in the ballot box.

“Disasters typically increase voter turnout. Either people are really pissed or they’re thrilled — the government actually came through for them.”

— Daniel Aldrich, a professor of political science at Northeastern University

Over the next few months, we’ll be looking at how extreme weather, exacerbated by human-caused global warming, is having a transformative impact on elections — floods destroy polling places, wildfires displace voters, and long recovery delays erode trust in local and federal government. These disasters are also interrupting daily routines, school schedules, household finances, even where people work and live, all of which in turn have profound effects up and down ballots across the United States and indeed the rest of the world.

Disasters are influencing politics in the rain-ravaged northern French countryside, the flooded suburbs of southern Brazil, and the sun-scorched streets of Delhi. In communities around the United States, from deep-red Louisiana to bright blue California, and in races from city councils to the U.S. Senate, climate disasters are shaping elections, voting rights, and political engagement.

Aerial view of a flooded area of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil.

Nelson Almeida / AFP via Getty Images

We’ll bring you personal, narrative accounts from the front lines of the disaster-politics intersection, but we’ll also draw on the vast and growing body of research that examines where, and how, extreme weather events dictate voter behavior. Data from all over the world, including Pakistan, China, and the U.S., show that these catastrophes drive some people further into their political foxholes, prompt others to mistrust or even hate the government, and inspire many more to become more engaged in civic life.

“Disasters typically increase voter turnout,” said Daniel Aldrich, a professor of political science at Northeastern University. “Either people are really pissed or they’re thrilled — the government actually came through for them.”

Stick with us as we unpack whether flooding in Kentucky affected voter trust, how water wars in the western U.S. could help Democrats flip the Arizona legislature, what you can do to ensure your vote gets counted after a disaster hits your area, and more.

In the hot seat

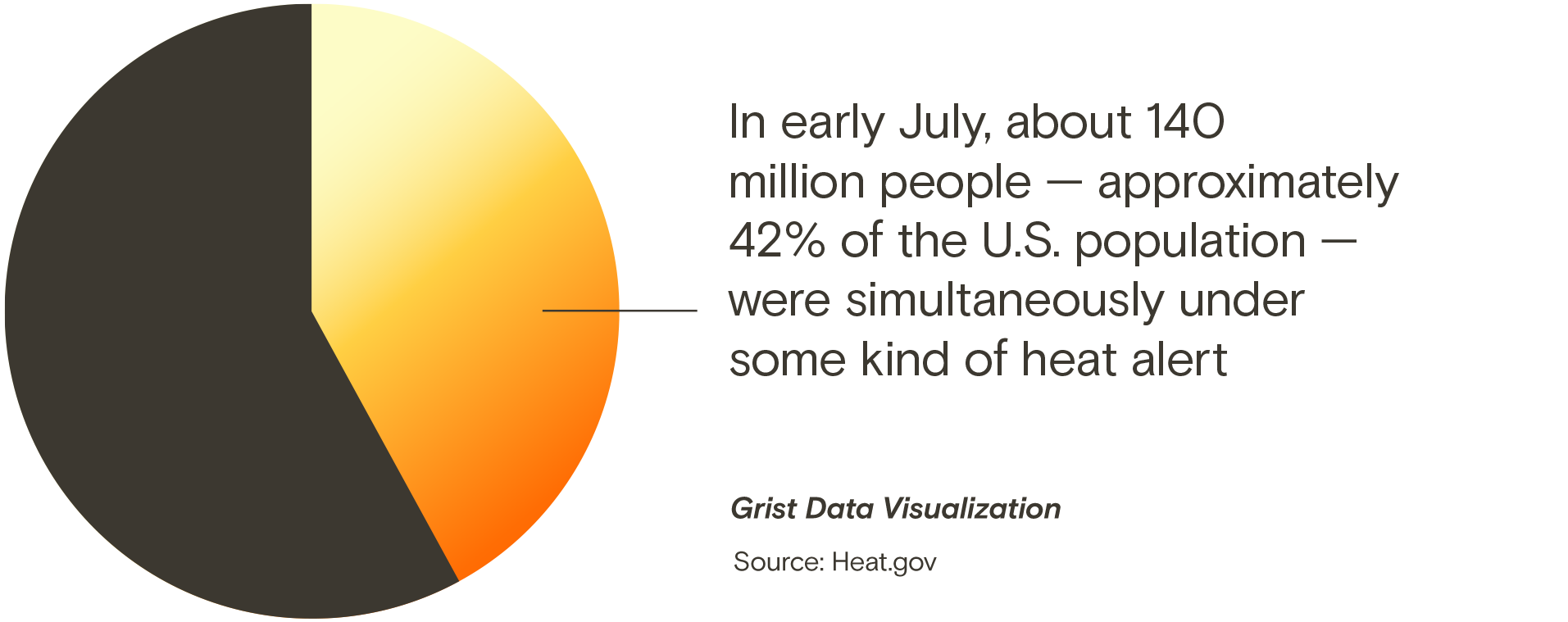

Summertime heat in the United States has always put human health at risk, but the past few years have marked the beginning of a new, far deadlier era. Heat waves fill emergency rooms with heatstroke victims, kill agricultural workers picking produce in America’s countryside, overwhelm older adults who don’t have air conditioning, endanger children and pregnant people, melt asphalt and rail tracks, and ground 400,000-pound airplanes.

A cadre of unelected officials across the U.S. are developing solutions to extreme heat that could save lives. But mounting a coordinated response to extreme heat in a country where everything is politicized is suffering from the same affliction that has sounded the death knell for climate action in a thousand other forms: denial. State politics are getting in the way of smart policies. Read more here about America’s chief heat officers, and the partisanship inhibiting their efforts.

What we’re reading

Hurricane Debby makes landfall in Florida: The Category 1 storm hit the Sunshine State’s north coast in the early hours of Monday morning before weakening into a tropical storm. Parts of Florida’s rural and sparsely populated Big Bend region are still recovering from last year’s Category 3 Hurricane Idalia, which struck the same area of the coast. By late Monday afternoon, Debby had been linked to at least four deaths in Florida, while Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina were bracing for potentially record-breaking flash flooding. Read more

Read more

The United Houma Nation gets $56.5 million to become more resilient: Louisiana’s largest Indigenous tribe got a big grant from the federal government to enact a climate-resilience plan that the tribe says could serve as a blueprint for other places. The tribe aims to build resilience hubs, a communication network, and a migration plan to help its 19,000 citizens adapt. Josie Abugov has more on NOLA.com. Read more

Read more

An ad campaign urges swing state voters to think about “unnatural disasters”: Science Moms, a group of scientists, launched a $2.5 million ad campaign in Wisconsin and other states that highlights the role climate change plays in worsening disasters. In CNN’s opinion section, Anita van Breda, senior director of environment and disaster management at the World Wildlife Fund, explains “why there is no such thing as a ‘natural’ disaster.” Read more

Read more

Torrential rains kill more than 250 people across Asia: Scores are dead in India and China and three people died in Pakistan as monsoon rains exacerbated by climate change sweep across the continent. Hundreds of people are still missing with rescue efforts underway. Earlier this summer, flooding stranded 1.8 million people in northeast Bangladesh and heavy rain in India killed more than 10 people. Read more

Read more

What to do when disaster strikes: When sirens wail, notifications pop up on your phone, and your state declares a state of emergency, what do you do? Where do you go? What do you bring? Vox has you covered with a new guide. Read more

Read more